Watt’s Up

Are you confused by all the specs? Are you trying to sort it all out? You are not alone. It isn’t easy to understand. We get lots of folks asking about the various specifications and classifications. This article sorts through a few of the most often-asked questions and takes a stab at making it easy to understand.

First, the classifications:

- Class One e-bikes only help you pedal up to 20mph. After 20mph, you are on your own. There is no throttle.

- Class Two e-bikes also help you pedal up to 20mph, but you get a throttle.

- Class Three e-bikes allow you to pedal up to 30mph and may have a throttle option, but the throttle is usually limited to 20mph.

There are many choices: front motor, rear motor, center drive, urban, mountain, or commuter. For more on what type of configuration or bike to choose, check out the Top Ten E-Bike Options blog. No matter your choice or specification, you must ride the bike to decide.

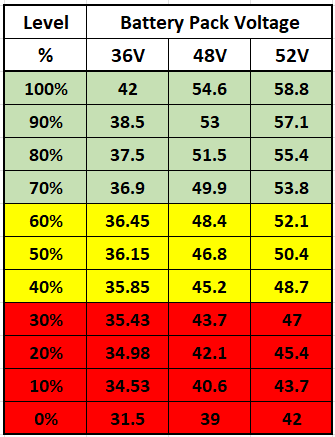

VOLTS. This is easily the most common specification compared. Morning jolt or decaf more is usually better. But, higher octane comes at a higher price. Think of volts as the push or force provided by the battery. 24, 36, and 48 volts are the most common. Twelve volts is best kept to scooters and toys. Higher voltage systems are better at getting the power from the battery to the motor. The wire has resistance, and volts are lost as they travel to the motor as heat. The closer the motor is to the battery, the better, at least for voltage drop. You will notice as the battery is depleted, you get less distance. That is because the motor controller tries to maintain the same power level but with less voltage. Unfortunately, below a certain threshold, the motor controller turns off for protection. You can never use all the battery voltage.

RESISTANCE. As the name implies, resistance is the difficulty the electric circuit has getting to the load, where the real resistance, the motor, does the work. Not to be confused with my 20-year-old’s reluctance to do chores, but nonetheless, similar in result—the work doesn’t get done. The greater the distance the battery is from the motor, the bigger the wire needs to be to avoid the voltage being reduced, and the less current (amperage) makes it to the motor. Basically, you are heating the wire instead of turning the motor. That is why higher voltage systems are more efficient.

AMPS. Amperage is more like the current in a river. Electrons flow and transfer energy along a wire circuit. Higher voltages push more current, which results in more energy transferred into motion. Voltage pushes amps to cause the motor to turn and do work.

WATTS. The amount of work the electricity does is measured by watts. However, some energy is lost through heat. Poorly made motors can consume a lot of energy and not do much work. As such, just because a motor has a high wattage does not necessarily mean it will perform well. The motor could just sit there and get hot. Furthermore, you may not need much wattage to propel your ride. Typical wattage ratings are 250 watts to 750 watts. (Over 750 watts is not considered a bicycle in most jurisdictions; it’s a moped or motorcycle.) Some of the newest e-bikes come with lower, not higher wattage. Now, you might find a very lightweight bike, with a smaller battery and motor, that performs nearly as well as a similar older, and heavier bike.

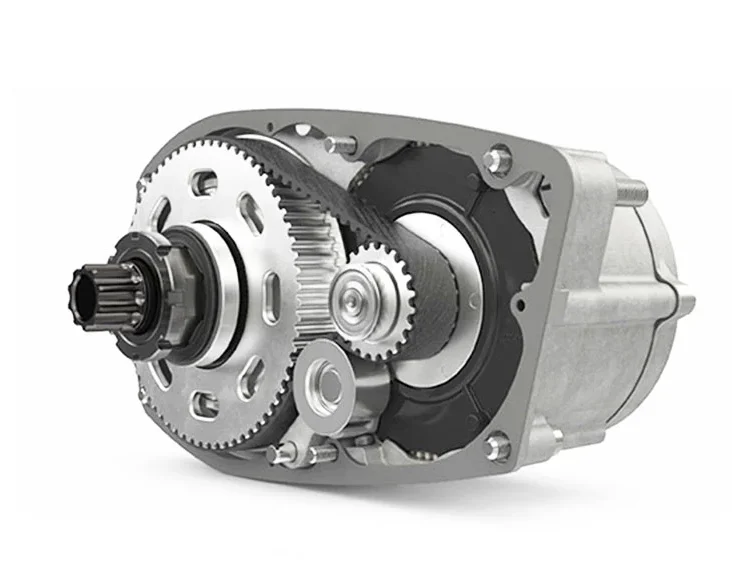

TORQUE. This is a twisting force. A motor’s torque is a good measurement to compare its ability to twist the wheels of the bike. Many bikes now list their torque spec. Typical levels are 50 Newton-Meters to 120 Newton-Meters (37-89 foot-pounds). That’s a ton of torque! Unfortunately, like many specs, there is no universal measurement standard. Torque is leverage, and that leverage ratio can be changed through gearing. That’s why center-drive motors have lower wattage ratings – shifting changes how the torque is applied. The torque also changes as the RPM changes. As a result, it’s hard to compare one motor’s performance to another using only torque as a guide. More is not necessarily better. After about 120Nm of torque, the motor puts tremendous stress on the drive train. Go above 120Nm, and you have a motorcycle. For example, some 2,000-watt “E-Bikes” look like bicycles and go very fast but are considered motorcycles in most jurisdictions. Technically, they may only be operated off-road. As with anything, it’s best to take a ride and decide.

WATT-HOUR OR AMP-HOUR. As the name suggests, it’s the amount of energy in a battery that is delivered over time. For example, a 10Ah battery will deliver about 1 Amp of current for ten hours. Similarly, a 500Wh battery will deliver 100 Watts of work for five hours. If you know the battery’s voltage, you can convert the specification. A 10Ah, 36v battery has 360Wh of energy (Watts = Amps X Volts). Generally, as the power demands increase, so should the voltage and Amp-Hour rating.

ENERGY. We always get this question: “How far will it go on a charge?” Most e-bikes will go twenty to fifty miles on a charge. Several factors affect mileage. Obviously, the more you do the pedaling, the farther you go. Two massive things work against you: wind resistance, speed, and weight. The faster you go and the more you weigh, the shorter your distance. Other factors include tire type, tire pressure, motor efficiency, battery size, battery age, hills, wind, and temperature (batteries work best around 60 degrees, +/-30 degrees).

PRICE. The specifications of a given e-bike are usually prominent. Actual performance may not reflect the specifications. Price is highly proportional to Volts + Amps + Watts + Watt-hours. Simply stated, you get what you pay for. The battery is the most expensive part of the e-bike. An inexpensive battery and motor make for an inexpensive e-bike. If you only want a casual ride every so often and have a limited budget, maybe a Nakto will do. If you are looking for a mid-priced bike, look at Aventon or Magnum. For the best ride experience and quality, look at Specialized Turbo.

That’s the basics. If you still crave more, read: E-Bike FAQs.

Copyright Randy Archer 2020